The intelligent article titled, “Munali and Lusaka Central: the appeal cases that reveal a court system in crisis” makes an interesting reading. It brings out issues, myths and conspiracy theories worth thinking about. It appears the nation’s anxiety has been raised over the long overdue decision in the Munali and Lusaka Central Parliamentary petitions by our Constitutional Court. In the final analysis, I make a reflection on the circumstances under which the two members of Parliament can be barred from re-contesting their seats if, by any chance, those seats are nullified. People should not be excited as yet in what may happen to any MP whose seat is nullified.

First comrade Sishuwa raises two issues pertaining to hearing and disposal of cases for Munali and Lusaka Central held by Ministers, Hon. Nkandu Luo, MP and Hon. Margaret Mwanakatwe, MP respectively by asserting that (1) the Constitution has gaps in its failure to set the time for hearing the case but also that (2) the procedure of appealing cases from the High Court to the Constitutional Court is a fundamental error in law.

Much as I agree with him on the first point that we should have set the time limit for disposal of appeals, I don’t agree with him on his second point that a fundamental error in law was made where an appeal in a Parliamentary petition lies to the Constitutional Court.

First, we ought to understand that the election of Councillors, MPs and President is a constitutional issue set by Article 47 of the Constitution of Zambia.

So while the local government petitions are heard by a Local Government Elections Tribunal and Parliamentary petitions are heard by the High Court as per Articles 159 and 73, respectively, the question of election of councillors, MPs and President, being a constitutional matter is required to be determined by the Constitutional Court.

This is fortified by provisions of Article 1(5) which states:

“1(5) A matter relating to this Constitution shall be heard by the Constitutional Court”.

To give the Supreme Court jurisdiction to hear a constitutional issue of electing councillors or an MP thorough an appeal from a Court of Appeal would have raised a constitutional problem on jurisdiction of courts.

By a similar reason above, the Court of appeal is estopped from hearing an appeal on a constitutional issue raised in any court below. The provisions of Article 128 (2) which read:

“128 (2) Subject to Article 28 (2), where a question relating to this Constitution arises in a court, the person presiding in that court shall refer the question to the Constitutional Court”

The authorities above must settle the question raised as to the alleged fundamental errors in law.Needless to mention that if we had a situation where a Local Government petition had to start from a Tribunal to the High Court and moved to the Court of Appeal and finally to the Supreme Court or constitutional court, how long would it really take to settle the petition? Wouldn’t the same people be accusing President Lungu and his Patriotic Front party, even more, that they are the ones delaying the disposal of these petitions?

On the issue of the petitions having taken long, comrade Sishuwa, appears to mix facts with both some mythical conclusion based on the conspiracy theory in which he seem to allege that the PF appear to have a hand in handling of appeals by the Constitutional Court.

Indeed, it is a good call by comrade Sishuwa that we must have timeframe for hearing these appeals by the ConCourt. However, issues that need to be pointed out and require our careful and sober reflection here is the need for this final court of appeal to arrive at a good, just and acceptable conclusion based on facts that were adduced before the trial court and also based on careful understanding of the new law that governs nullification of an election.

First, I seek to remind Zambians that our law entirely places the handling of a client’s case on advocates and if lawyers don’t exercise due diligence, urgency and vigilance, the courts can do only as much to remind lawyers that it won’t tolerate delays.

This is articulated in Rule 36 of The Legal Practitioners’ Practice Rules, 2002, Statutory Instrument No. 51) as quoted below:

“36. A practitioner when conducting proceedings at Court:

(a) Shall be personally responsible for the conduct and presentation of the client’s case and shall exercise personal judgment upon the substance and Purpose of statements made and question asked;

(b) shall ensure that the court is informed of all relevant decisions and legislative provisions of which the practitioner is aware whether the effective is favourable or unfavourable towards the contention for which the practitioner argues and shall bring any procedural irregularity to the attention of the court during the hearing and not reserve such matter to be raised on appeal”

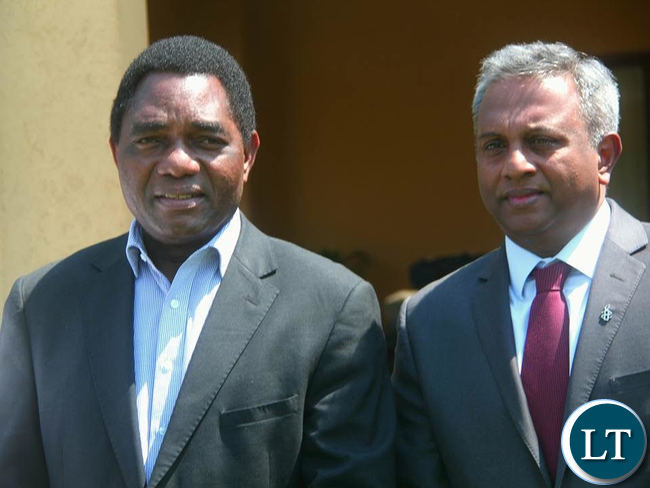

From this Rule, one should easily tell about who and what could have been behind the failure by the Constitutional Court hearing the 2016 Presidential Petition of one Hakainde Hichilema and Godfrey Bwalya Mwamba. Yes, the Court had its own inconsistencies in interpreting the law and giving directions but that does not absolve the petitioners’ advocates from sharing in the blame by failing to handle their client’s petition. As officers of the Court, did they help the Court, as required by Rule 36(b), to read the 14 days correctly?

I know this is a bitter pill for most of my UPND friends and I don’t mind being insulted for bringing this out, but once some of them sober up, they get to realise it was the primary problem of their lawyers who failed to take charge of their client’s petition while the Court’s problem was a secondary one.

I always laugh when my best friend tells me, “for lawyers, the more time one spends on a client’s case, the better the balance sheet at the law firm.”

Secondly, it must be realised that the ConCourt decision in all appeals from electoral petition has far-reaching implication where an MP whose seat falls vacant by disqualification, as a result of a decision of the Constitutional Court, is not eligible to contest an election or hold public office by operation of Article 72(2)(h) as read with Article 72(4).

In light of the weight such a ConCourt decision carries, some myth and conspiracy theories must be discarded in our analysis of how the court handles these appeals. It is true that our Constitution, in Article 118 (2)(b), require that justice is not delayed. This principle require a careful balance found in Article 118 (2)(a) which states that “justice shall be done to all, without discrimination”

In doing justice to all, especially making decisions that will have an effect on the future of MPs in question to serve their country either in Parliament or public service, it is important that decisions are not hurriedly made but also that even the person being barred must appreciate the decision that barred them from serving again.

Finally and most controversial of this topic would be explore the legal discourse on the correct meaning of Article 72(2)(h) as read with Article 72(4).

In part, these articles read:

“72(2)(h): The office of Member of Parliament becomes vacant if the member is disqualified as a result of a decision of the Constitutional Court”

“72(4)A person who causes a vacancy in the National Assembly due to the reasons specified under clause (2)(h) shall not, during the term of that Parliament-

(a) be eligible to contest an election; or

(b) hold public office.”

The plain reading of these articles suggest that once a seat is nullified, the person holding the seat is not eligible to stand and to be appointed to public office. However, there is a second meaning, which I think is more correct to these two articles.

These articles are different on the following grounds. The first one talks about how a member vacates his or her seat while the second one talks about what happens to the person who causes vacancy based on the decision of the ConCourt.

It is possible that the Court may nullify an election, say in Munali Constituency, based on the violence of supporters which made the election to fail the test of being free and fair but at the same time exonerate the incumbent as not having been the cause of the violence. This would fail the test of “A person who causes vacancy…”

I submit that for any Member of Parliament to come under the ambit of Article 72 (4), it would require the Constitutional Court pronounce itself that indeed, the incumbent is that “person who caused the vacancy” thereby going beyond the mere nullification of a seat to making a declaration that a member is “disqualified”. A vacancy caused by any other reason such as “other persons e.g. cadres involved in political violence” would not bar or stop an MP from contesting elections or getting an appointment to public office.

(The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent any institution I may be associated with and neither is it meant to offer a legal opinion. Those seeking a legal opinion can contact the Law Association of Zambia, which is an authority of legal matters)

By Isaac Mwanza