Chilenje Level 1 Hospital in Lusaka to soon be converted into a COVID-19 treatment centre, Ministry of Health Permanent Secretary for Technical Services Kennedy Malama has revealed.

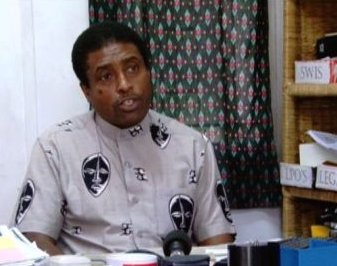

Dr Malama said during the routine COVID-19 update in Lusaka yesterday that the move is intended to increase the space of COVID-19 treatment centres.

“In our quest to increase space we will be converting Chilenje Hospital in Lusaka into a COVID -19 treatment centre in the coming days. To stem further spread of COVID 19, let us all take that critical step to adhere and enforce the five golden rules in all our circles,” he said.

And the Permanent Secretary noted that the sad picture in terms of lives lost on a daily basis due to COVID-19 in the country remains worrisome as he announced that the highest ever number of deaths since the beginning of the pandemic, of 61 new deaths were reported in the last 24 hours.

He added that 3,594 new confirmed COVID-19 cases out of 12,880 tests conducted giving a 28 percent positivity were also recorded in Zambia in the last 24 hours.

Dr Malama highlighted that the breakdown of new deaths by province shows that Lusaka recorded 20, Copperbelt and Southern 12 cases each, Eastern eight, Western three, Central and Northern two each and Luapula and North-western provinces one each respectively.

“As you can see, all our provinces except Muchinga reported deaths in the last 24 hours, yet another stark indication of just how dire our situation is,” Dr Malama observed.

He indicated that the cumulative number of COVID-19 related deaths recorded to date now stands at 1,855 classified as 1,194 COVID deaths and 661 COVID-19 associated deaths.

“Of all the deaths recorded over the course of the pandemic, 574 representing 31 percent have been recorded in the month of June alone,” he stressed.

Meanwhile, Dr Malama stated that the cumulative number of confirmed cases recorded to date is at 140,620.

He said a total of 100 districts reported cases of COVID-19 with 69 districts reporting 10 or more cases adding that Lusaka is the epicenter, contributing an average of 31 percent of the daily disease burden.

“The breakdown of the new cases by province are as follows, Central 464, Copperbelt 366, Eastern 435, Luapula 111, Lusaka 1,130, Muchinga 149, Northern 179, North-western 105, Southern 278 and Western 377,” he indicated.

And the Permanent Secretary stated that 2,789 discharges were made in the last 24 hours which included 104 from isolation and treatment health facilities and 2,685 from home management, bringing the cumulative number of recoveries to 115,898.

“Further, in the last 24 hours, we had 220 COVID-19 admissions to the healthcare facilities nationally. We now have 22,867 active cases, of whom 21,624 are under community management and 1,243 are admitted to our COVID-19 isolation facilities.

Dr Malama pointed out that among those currently under admission, 856 are on oxygen therapy and 176 are in critical condition.

He observed that the country has continued to see high admission rate on a daily basis, with the number averaging over 200 each day for the past week indicating that the COVID -19 is widely spread in the communities.

“The good news is that we can change this narrative in the next three weeks if we worked as one and transferred the fight from our hospitals to the communities,” the Permanent Secretary noted.

He added, “We cannot bend the COVD 19 cases, admissions, and deaths curve from hospitals but from our communities. We all have a role to play at individual, family, institutional and community levels.”