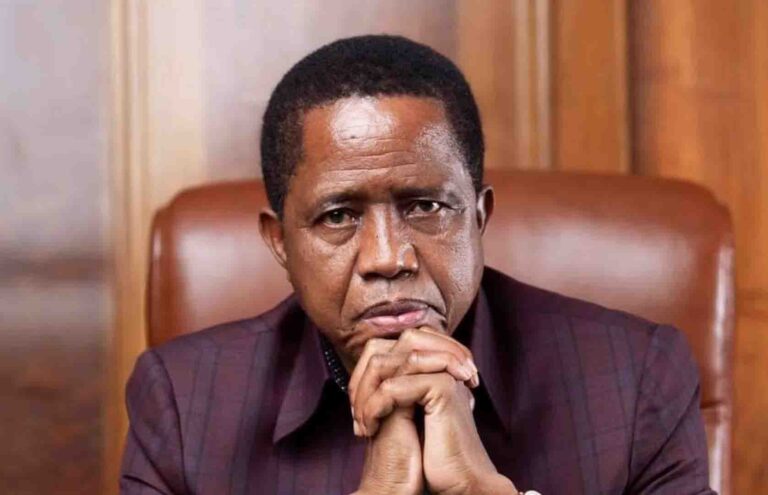

Constitutional Court Declines Direct Appeal in Lungu Burial Dispute

South Africa’s Constitutional Court has refused an application by the family of former Zambian President Edgar Chagwa Lungu to appeal directly against a Pretoria High Court order regarding the repatriation of his remains. The ruling, delivered this week, underscored that litigants must follow established judicial procedures and cannot bypass lower courts to access the country’s highest tribunal.

In its pronouncement, the Constitutional Court was categorical:

“The Constitutional Court has considered the application for leave to appeal directly to it and has concluded that no case has been made out for a direct appeal. Consequently, leave to appeal must be refused.”

The order further stated: “Leave to appeal directly to this Court is refused.”

Why the Court Said No

The decision was not a ruling on the substance of the burial dispute but a procedural one. South Africa’s apex court allows direct access only in cases of exceptional urgency or questions of major constitutional importance. The judges concluded that the Lungu family had not met this threshold.

As a result, the Pretoria High Court’s earlier order, which directed that Lungu’s remains be repatriated to Zambia for burial, remains standing. However, because the Constitutional Court has declined direct involvement, the matter now returns to the ordinary appeal process. The family must first seek leave to appeal through the Gauteng High Court, and if unsuccessful, they may escalate to the Supreme Court of Appeal. Only after exhausting those routes can the Constitutional Court consider the case again.

This layered process illustrates the principle of judicial hierarchy. By rejecting the direct appeal, the Constitutional Court has reinforced the importance of due process, making clear that litigants cannot simply “jump the queue” when the law prescribes a step-by-step procedure.

What It Means for the Burial Dispute

For the Lungu family, the ruling is a setback. It narrows their immediate legal options and removes the protective shield that a Constitutional Court intervention might have provided. While they can still pursue ordinary appeals, those processes are slower and less likely to prevent enforcement of the Pretoria order in the short term.

For the Zambian government, the decision strengthens its legal position. Officials in Lusaka have insisted that former presidents must be buried at Embassy Park, the official presidential burial site in Lusaka. President Hakainde Hichilema recently reaffirmed that this is both a legal and symbolic requirement, underscoring national unity and continuity. Yet, the government still faces the delicate political task of managing optics and family sensitivities.

Tensions remain visible. On Sunday, the Zambian government announced it was engaging the family in dialogue. But family lawyer Makebi Zulu told reporters that the family was “in prayer” and not participating in negotiations. The disconnect between official statements and the family’s position highlights the mistrust still surrounding the matter.

Wider Context and Implications

The dispute has generated intense public debate, with some commentators warning that legal wrangling may drag on for months. One observer noted that the family “went straight to the Concourt to stop the body from moving,” but the judges’ decision sends a clear message: follow procedure first.

Until every stage of the appeal process is exhausted, the Zambian government cannot act unilaterally. For now, Lungu’s body remains in legal limbo, underscoring the intersection of law, politics, and national symbolism.

Beyond the courtroom, the episode has also prompted reflection on broader priorities. Analysts argue that while the dispute commands attention, Zambia faces urgent challenges in hunger, energy shortages, and economic strain. The Constitutional Court’s refusal serves as both a procedural reminder and a subtle call to patience: justice will run its course, but in the meantime, citizens must focus on pressing national needs.

The Road Ahead

The Lungu family now faces a choice: file for leave to appeal in the High Court and, if denied, pursue the matter in the Supreme Court of Appeal. Should those efforts fail, the Constitutional Court may revisit the case, but only through the proper channels.

For now, the Pretoria High Court order stands, but enforcement remains suspended while the legal process continues. The Constitutional Court has closed one door, but the case itself remains alive , a dispute straddling the lines of law, politics, and legacy.