By Kalima Nkonde

Zambian national, Mwansa Prospery Chalwe, has just published the above intriguing, thought provoking and well researched book on Amazon.com, in both paperback and e-book versions. The book demonstrates how China and the West are in a stealth “war” of influence on Zambian soil without most citizens and our politicians realizing it. The book should be an eye opener to ordinary Zambian citizens, policy makers in the US/West, China, Africa and Zambia. In this article, I will carry out a brief general review of the book.

The book has dissected and unravelled the causes of Zambia’s economic problems that have turned the country into a basket case within a space of 10 years. He has somehow, intelligently linked the country’s economic crisis to the geo-political and economic rivalry of the West and China which gives the book an international flavour, without necessarily, losing its local relevance.

The book is mainly anchored on Zambia’s debt crisis which has resulted in the country being the first Sub-Saharan African country to default on its Sovereign debt post COVID-19. It outlines how the country went on a borrowing binge from both the West and China from 2012. It then goes to document how the two main categories of creditors have since been fighting over the restructuring of the country’s foreign debt. He also outlines the role of the International Monetary Fund, and interestingly and perhaps surprisingly, the United States Senate which is unknown to most people in the debt restructuring process.

The Author first analyses the performance of the Zambian economy for the past 10 years. He then takes the reader on a journey on how Zambia borrowed its way into economic turmoil. One of the first decisions that new PF administration took in 2011, was to embark on the ambitious, massive infrastructure development. The Author, in a very simple and layman language, shows why the PF infrastructure programme which was debt funded, has not produced the economic growth and created jobs which such programmes normally produce all over the world. He has, in fact argued that the infrastructure programme, is one of the major causes of the economic problems that Zambia is facing today. He calls it the poisoned well of the economy.

The issue of corruption has been handled in two chapters. He has provided empirical evidence using econometric studies which show how corruption can ruin any country’s economy in the world with numerous examples, and how it has done the same to Zambia which should not be surprising to those knowledgeable.

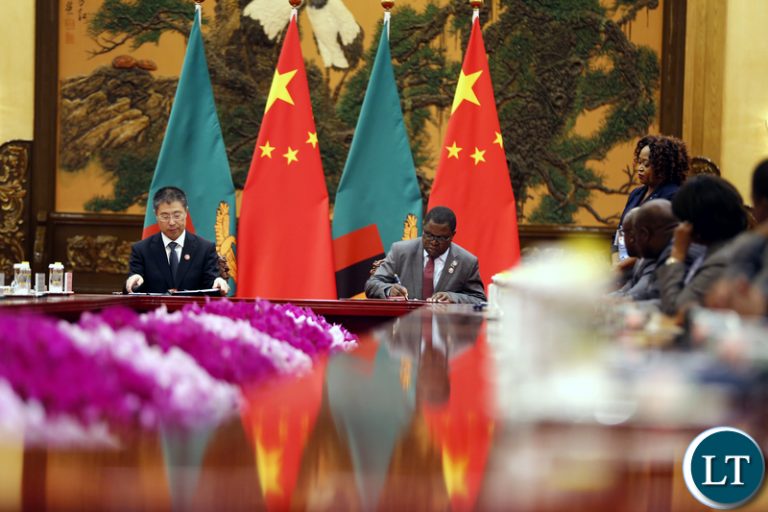

The book does not take sides between the West and the Chinese and he criticizes both. The Author argues that both the West and China are in Zambia to pursue their own interests and it is up to Zambian leaders to negotiate deals that are in Zambian’s best interests. According to him, both the Washington consensus and the Beijing Consensus development models in their purest form, are not suitable to Zambia and Africa as African societies are complex and their environment are totally different.

He first criticizes the West and the IMF for its Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) of the 1980/90s, which was based on the Washington consensus of free markets. The model destroyed Zambia’s industrial base and has resulted in the country being over dependent on imports thus being responsible for some of the current economic problems.

In regard to the Chinese, the book shows that Zambia is among the closest African country to China, to the extent that some analysts argue that Zambia is China’s poster child in Africa. The close relationship is supported by economic, political, diplomatic ties that date back close to 60 years. And the closeness is shown by the large number of Chinese immigrants. In addition, the fact that Zambia is one of few countries with the Bank of China branches in Lusaka and Copperbelt is further evidence of the closeness between the two nations. The Zambian government’s failed attempt – due to public outcry- to recruit Chinese nationals in the Zambia Police Service is another factor that some people point to, as a demonstration of how entrenched Chinese influence is in Zambia.

The Author argues that the current economic relationship between China and Zambia benefits China much more than Zambia. The “win-win” situation claimed by China, is a mirage according to him. He demonstrates with supporting facts how the Chinese development financing model in its current form, has not benefited Zambia but China. He argues that the billions of Chinese dollars of debt finance have not resulted in much multiplier economic activities in Zambia to create jobs and reduce poverty. He suggests that Zambia and China need to recalibrate their relationship so that it is mutually beneficial with the bottom line being poverty reduction as the key metric.

In the regard to the United States of America’s role in its competition with China in Zambia, he shows that whereas China’s influence in Zambia is focused on lending and infrastructure, the US has invested heavily in “soft power” of AID with negligible commercial presence through its private sector. The book shows the billions that America has poured into Zambia which has saved millions of lives. The US contributes huge sums to Zambia’s health care budget. The US’s PEPFAR programme is one that millions of ordinary Zambians have benefited from. It has literally kept some people alive. He has also noted the Biden administration’s plan to reset its economic policy in Africa in response to Chinese influence and suggests how the US can economically compete with China on African soil.

There is an interesting chapter where he demonstrates that in Zambia’s 57 year history, there is a correlation between economic performance and democracy and human rights. Zambia’s economy has performed better in an open democratic environment where political and civil rights have been protected and safeguarded. In the past ten years, there is sufficient evidence that the country’s democratic credentials have been eroded thus contributing to the poor performance of the economy.

The book proposes a number of solutions for African development which he calls: “21st Century Afro Development Initiatives (ADIs)”. He controversially argues that infrastructure should not be one of the top priorities apart from as it relates to Agriculture and electrification especially for rural areas. He also argues the aggressive promotion of foreign direct investment on current terms as it is not beneficial and believes that it is better to keep the minerals in the soil for future generations.

The book’s conclusion is on the World’s current health and economic crisis- the COVID-19 Pandemic. The on-going rivalry and competition between the US and China with regard to vaccine diplomacy and the origins of the virus puts the title of the proper in proper context.

In a nutshell, as far as the Zambian economy is concerned, the book argues that although the debt crisis is the major cause of Zambia’s economic crisis, there are other factors. These include the lack of sufficient benefits from foreign direct investment, illicit financial flows, corruption, and deterioration in democracy, low copper prices and drought in some years, the current Covid-19 and above all the poor leadership on both sides of the aisle. These are issues that those vying for power and the Zambian people ought to address.

Chalwe has taken no prisoners in this intriguing and interesting book. It is a must read book for both the international and local audience in the light of the current rivalry between China and the West, the COVID-19 Pandemic, the forthcoming Forum of China and African Cooperation( FOCAC) conference in Dakar, Senegal in September this year and Zambia’s economic crisis.